Jim Brown was NAUI Director of Training in the 1980s and ’90s. This article appeared in the July 1990 of Sources.

Have you ever observed a diver in distress on the surface? You might remember some classic signs — no air in the BC, mask on the forehead or gone, mouthpiece missing from the mouth, the head just barely above the water, no buddy present and not one sound uttered. What did you do?

We know from our training and experience that being prepared to conduct a rescue is as important as recognizing problems and techniques used to solve them. Preparation includes “global awareness,” proper equipment, a predetermined and agreed-upon emergency plan and a “chain of command.” We are also aware that the most common problems requiring rescues occur on the surface and involve anxious divers who are having difficulty breathing properly and establishing buoyancy.

Our reaction usually involves implementation of an emergency plan and getting to the distressed diver as quickly as possible without overexertion. Upon arrival, we know establishing buoyancy is our most important goal. We are also aware that by the time we arrive, the distressed diver is on the verge of or is experiencing panic. Did we attempt to attract the distressed diver’s attention before making contact? Since this is common procedure, have we bothered to learn why?

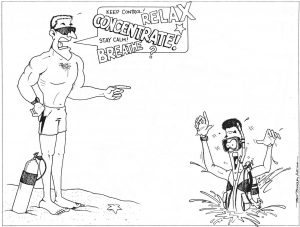

Unfortunately, some rescues of this nature seem to be noisy, confusing affairs with lots of shouting and running amok. It’s amazing how an emergency situation can create instant hearing loss in bystanders as well as participants. Why else would someone be shouting at the top of his or her lungs exhortations like: “You! Call for help!” or “You! Put your equipment on and follow me!” or “Hey, you out there, RELAX, DROP YOUR WEIGHT BELT, INFLATE YOUR BC!” Have we ever known a distressed diver to respond to such commands shouted from a distance? As a matter of fact, do we really need his or her attention?

The “quiet rescuer” would consider this scenario from the distressed diver’s point of view. If we could interview a “rescued diver” immediately, we would learn several interesting things: 1) The diver didn’t hear, much less understand, one shouted word. 2) The diver didn’t signal for help for fear of attracting attention and experiencing embarrassment. 3) The diver thought the question, “Are you OK?” ludicrous.

Let’s go back to the point when a diver is identified as “in distress” and consider the “quiet rescue” technique. You may be in the water or on the boat or shore when you recognize a problem situation. First and foremost, remain calm and act quickly and with purpose. Avoid shouting! When you approach the distressed diver, try utilizing the following rescue sequence:

- As you draw near the distressed diver, distract him or her from the predicament by staying within the diver’s field of vision and speaking in a conversational tone. What we say is of little importance so long as how we say it projects a calm, friendly and sympathetic tone.

- Move in and touch the distressed diver immediately! Human contact in stressful situations has an immediate calming effect. Contact must be gentle but firm. You can gauge the effectiveness of your rescue efforts by “feeling” for a reduction in muscle tenseness. Remember to establish personal buoyancy during your approach, so you can share it with the anxious diver and meet the goal of establishing the diver’s buoyancy.

- Now that you have the diver’s attention, it is time to say something meaningful and useful since there is a better chance of comprehension. Talk to the diver using reassuring phrases (“You are fine,” “No problem,” etc.) while inflating the BC, ditching the weight belt or whatever the situation warrants. The goal is to make this seem natural and unobtrusive — no big deal.

- As you talk, give simple instructions designed to get the diver’s breathing under control (“Breathe slow and deep.”). You might even demonstrate proper breathing by exaggerating your own. The new goal is to establish proper smooth breathing and have the diver relax. Patience is a virtue in this instance. It takes time to calm a diver emerging from panic or near panic. If there is time available, use it. You can begin a leisurely swim back to your exit point, stopping to rest as needed.

A casual observer may never know that a rescue has occurred. If you’re concerned about the diver, you probably won’t mention the word “rescue” at all. Most likely, you’ve gained a grateful friend who will listen to sound advice that may prevent a reoccurrence of similar problems in the future.

As NAUI Instructors, we are taught the importance of meeting the needs of our students. In a rescue situation, shouldn’t we also concern ourselves with meeting the needs of others? The distressed diver may not be a student, but we are still diving professionals who can take control of emergency situations and demonstrate effective leadership.

The quiet rescue technique discussed is based on the basic first-aid principle of “do no further harm.” We are all too aware that a tired, distressed diver can quickly become a drowning victim. When a rescue is necessary, we can use these techniques, effectively downgrading the “full-blown, hands-on rescue” to an assist and, eventually, to a self-rescue. We may not look like heroes, but we will have acted in the professional, responsible manner that is the hallmark of all NAUI Instructors.

Egos are fragile things. We can damage the egos of others while feeding our own. That’s not to say that we must preserve a diver’s ego at the expense of losing his or her life. We can, however, recognize stressful situations for what they are and deal with them quickly, efficiently and quietly. After all, personal “ego embolisms” are difficult, if not downright impossible, to treat!