I found myself getting bored with diving. I had been diving within no-decompression limits for several years, and I could not find the next challenge or another skill to learn. A Course Director told me about two instructors running technical diving classes and wreck diving. I had previously ruled out technical diving because the complexities and risks associated with decompression and overhead environments made me nervous. For whatever reason, I decided to look up the instructors. The journey they started me on continues to this day, and it has completely reinvigorated my passion for diving. Along the way, I have found some wonderful friends, explored amazing sites, and changed the way I dive and teach.

As with most divers exploring technical diving, we started with the “Introduction to Technical Diving” class. I was guided through equipment selection and configuration and introduced to some new topics. After some practice with this new configuration using double cylinders and a long hose on my regulator, we started the next class: decompression procedures, advanced nitrox, and helitrox.

Now I could join the group in diving wrecks, and in the process, I learned about the history of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Bay has been an active maritime center since the Plymouth settlement in 1620. There are likely hundreds of wrecks in Mass Bay. The ships include large schooners, tugs, work lighters, western and eastern rigged draggers, tankers, passenger steamships and a variety of naval vessels reflecting the maritime history of New England. Divers explore Mass Bay trying to locate and identify the sites.

I started diving wrecks in the 100-foot range. These sites are accessible to divers who stay within no-decompression limits, but divers who have appropriate training and equipment will be able to take advantage and stay longer.

The Chester Poling was a 281-foot (86-meter) coastal tanker used for transporting heating oil. In 1977, she broke in two during a storm. The bow turtled and sank in 190 feet (58 meters). The stern floated for several miles and sank upright in 95 feet (29 meters). Divers can enjoy swimming around the wreck or explore another wreck that is within swimming distance.

The Patriot was a 62-foot (19-meter) western rigged dragger built in 1997 that sank in 2003 in 100 feet (30 meters). There is abundant marine life found on this site. Even humpback whales were next to the wreck on a recent dive!

The Pinthis was a 110-foot (35-meter) steel coastal tanker built in 1919 for transporting oil, now lying turtled in 105 feet (32 meters). Divers can easily access the daylight zones or penetrate for the full length.

While these dives are fun and exciting for us, it is important to remember that crewmembers have lost their lives when serving these vessels. As divers, we should be respectful when visiting and posting on social media.

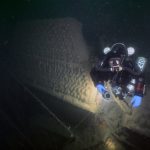

My curiosity got the best of me, and I wanted to look inside these wrecks. To train for wreck penetration, I completed classes to learn how to plan safely and navigate overhead spaces. Instantly, every wreck I had ever explored had new areas to be explored. The Poling has living quarters and galley on the first level with ambient light, multiple exits and easy navigation. The next deck down is the engine space, which has become silted in and my exits are typical with little to no visibility. The equipment and decking of the Pinthis lie on the bottom with the turtled hull overhead.

I started becoming curious about deeper wrecks and knew it was time to start working on trimix classes. This training allowed me to explore the deeper wrecks in Mass Bay.

The Coyote was a 267-foot (81-meter) wood freighter built in 1915 as part of the war effort. She was scuttled in 1932. Divers today find her in 170 feet (52 meters) of water. While swimming along the centerline, divers can observe both sides of the ship including a triple expansion steam engine and associated equipment.

The Baleen was a 102-foot (31-meter) tug built in 1923. On October 31, 1975, there was a fire in the engine room that burned out of control. While burning, she was taken in tow, but after 16 hours the Baleen sank. Today, divers find the Baleen, a very iconic looking tugboat, sitting on her side in 170 feet (52 meters).

The LV 39 Brenton Reef Lightship was built in 1875 and is 119 feet (36 meters) long. She was constructed as a sailing schooner but had boilers, pump and fog whistle. She sank while under tow and lies in 180 feet (55 meters). Divers can explore from the outside or penetrate, revealing artifacts of its multiple uses, including its time as a restaurant and clubhouse.

The Snetind was a four-masted freight schooner, 234 feet (71 meters) long, built in 1919. Although she served many years hauling freight, local divers find the story of her life after hauling freight to be more captivating, revolving around a Mrs. Ann Winsor Sherwin. Mrs. Sherwin was from a “good family” and part of the “fashionable” Boston scene until her divorce. After the divorce, she eventually found herself living on the Snetind, where she also operated an arts and craft store. In 1936, the Snetind was moved from the wharf to a mooring under a court order. A winter storm in 1936 caused the Snetind to break free from her mooring and wrecked her on Spectacle Island. Mrs. Sherwin continued to live on the now wrecked vessel, but she was finally forced ashore due to illness. In 1951, the Snetind was towed out and scuttled in 190 feet (58 meters). Divers today find the wreck sitting upright with the hull structure stable. Evidence of her previous life abounds: divers can observe milk bottles, painting easels, and many other personal items.

The USS YF-415 was built in 1943 for service as a freight lighter. She was 132 feet (40 meters) long. On May 10, 1944, she was loaded with 150 tons of ammunition for disposal in deep water off Boston. The ship and 31 crewmembers arrived on site and started disposal operations. A fire broke out that spread to the entire main deck. The crewmembers did their best to fight the fire, but only 13 men survived. Today, the YF-415 sits in 240 feet (73 meters) with opportunities for exploring the entire wreck.

With so many exciting wrecks to explore, I found myself struggling with the logistics of diving multiple times a week with open circuit doubles. There are also limits to gas planning and management when diving deeper or longer. These factors lead me to start training on a closed-circuit rebreather (CCR). I did not anticipate how much CCR changed how I dive. More time is needed maintaining and preparing the equipment, but it pays off when we get multiple days of diving, when we choose to do a longer dive, or when marine life comes right up to this “no-bubbles” diver and checks me out.

The technical diving training I’ve worked through has completely changed my diving, my diving goals and even how I teach scuba. Along the way, I’ve visited some amazing places, explored spectacular wrecks and found great friends who share my passion and have been there to share in the adventures.