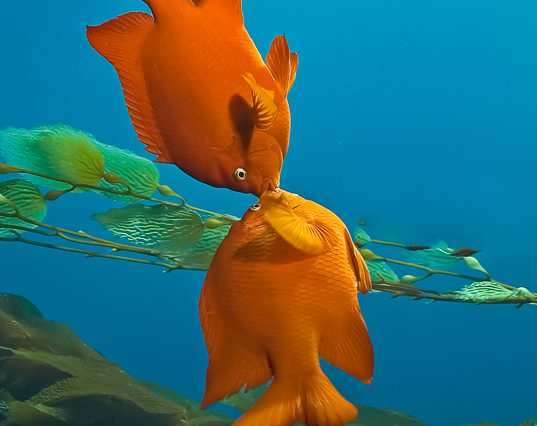

Whether by serendipity or making dives in which you look for specific behaviors, it is possible to find animals acting in interesting ways on many dives. For many experienced underwater photographers, creating images that reveal behaviors ranging from displays of territoriality, courtship, mating, egg guarding, hatching and nursing to predation, cooperative and opportunistic hunting, cleaning, camouflage, etc. is especially rewarding.

In this piece I am going to share some things that I hope will help you create the behavioral shots you seek.

When you see an interesting behavior, the first thing you should do is pause and analyze the situation. In some scenarios there is very little time to lose. But getting in a big hurry often works against success. Hurrying can cause you to move in a manner that frightens your potential subjects, thus disrupting their behavior, or to settle into a poor shooting position when a far more advantageous location is close by.

As you pause to assess, make sure you are neutrally buoyant so you do not accidentally crash into the bottom when you make your approach. Colliding with the substrate can cause you to lurch awkwardly, create noise that frightens your subject, and kick up sediment that leads to backscatter.

Depending upon the size of your subject, the image you want to capture, and the lens on your camera, the next thing to do is try to determine how close you need to get to your subject to compose a compelling photograph. Look at your surroundings to decide whether you should stay where you are or move to a location that will give you a better opportunity to capture the behavior. If you are going to move, check to be sure your gauges, hoses, belts, and straps are neatly tucked away so you don’t accidentally get “hung up” or bump into the substrate as you maneuver into position.

Next, set your camera controls to the desired shooting mode and exposure-related settings that you believe will allow you to acquire a proper exposure, and position your strobe(s). If you are going to move, try to establish your camera system settings and position your strobe(s) before making your way to a new position. This prevents you from having to move your camera system around when you are within “frightening distance” of your subject.

In short, pay heed to the advice given by the legendary basketball coach, John Wooden, when he told his players he wanted them to “be quick, but don’t hurry.” My suggestion to you is that you assess the behavior, evaluate the setting, make your best guess regarding how close you can get to your subject(s) without frightening or distracting them, and stop where you are or move to a good position to shoot from as quickly as reasonably possible — but without getting in so much of a hurry that you make a preventable mistake.

Now let’s assume you are in your desired position. My mantra at that point is compose and shoot as many frames as you reasonably can. As you shoot, look to see exactly what is taking place. If the action is unfolding as you anticipated, keep shooting. If it is not, you might want to alter your composition or position in a way that enables you to better capture the behavior that is taking place.

Depending on the particulars of a given situation, when I have an opportunity to capture behavioral images, I might shoot a number of frames at a given exposure, and then shoot a series of frames while increasing and decreasing my exposures by varying

degrees in an effort to make sure that at least some of my exposures will be on the money. Bracketing in this manner is much easier to do with subjects like mating nudibranchs that don’t move much than it is with a swimming shark that is being accompanied by a juvenile jack or a squadron of remoras. But I try to bracket my exposures whenever the opportunity presents itself, and suggest you do the same.

If you think you got your shot, before congratulating yourself and swimming away from the action, review your results. To do so, move your head away from your camera to check your composition, focus, and exposure on your camera’s LCD screen. Checking your results and making a needed adjustment can be the difference between getting the shot and an opportunity lost. You might discover that you want to make an exposure-related adjustment or try a different shooting angle or composition before swimming away.

Note that I am suggesting that you move your head away from your camera while holding the camera still, as opposed to pushing the camera away from your eyes and toward the subject. It is all too easy to disrupt behaviors by moving a camera system toward a subject when reviewing images.

Even if you have created a shot you are happy with, continue watching the behavior closely. You just might find the behavior to be much more nuanced than you first thought, and you might discover a different aspect of the behavior to photograph.

If I am the diver who finds the behavior, I often spend my entire dive photographing, watching, and learning about what is happening in front of me. If I am sharing the opportunity, I take a handful of shots, and then carefully move away making sure not to disrupt the behavior or stir up bottom sediment. After that, I often wait for another turn. For many underwater photographers, opportunities to capture behavior are precious. When you get your chance, stick with the “bird in the hand,” work that opportunity, and don’t worry about something else you might, or might not, be missing.

Last, but perhaps the most important advice I have for you is whether or not you get your shot, be sure to enjoy the process, not just your processed images.